Dr. Seamus Grimes is a professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Galway, Ireland.

Introduction

Although there is widespread concern throughout Europe during the current period of economic recession, with high levels of unemployment and the recent upsurge in refugee movements associated with the serious ethnic conflict in Eastern Europe, there is generally less awareness of long-term demographic developments which have been in process since the 1960s. The underlying trend towards low fertility is giving rise to significant imbalances in the population pyramid of Europe. This is illustrated by the increased aging of the population and the labour force. New policy measures to reverse the trend towards population decline are being recommended. This paper examines these recent trends in the population of Western Europe, focusing particular attention on the causes and consequences of fertility decline. Policy implications, including the likelihood of massive immigration into Western Europe, are also outlined.

Major demographic trends

The population of the continent of Europe in 1985 (excluding Russia) was 492 million, which was 10% of the world population and equal to the population of Africa (CEC 1991). The European Community, together with East Germany, constituted 70% of the total. By 2025, however, it is estimated that Europe’s share of the world population will be reduced to 6% and will be only one-third of the population of Africa. The main reason for this downward trend is that the European Community (EC) has experienced a fall in its birth rate of one-third during the last 20 years and is characterized by a relatively stable death rate. The population growth, therefore, fell from two million people per annum during the first half of the 1960s to 500,000–600,000 per annum during the second half of the 1980s. In the 1990s the Community‘s population is approaching zero growth and it will be in decline after 2000 (CEC 1991). Germany’s population has been in decline since 1974, while the United Kingdom (UK), Belgium, Luxembourg and Denmark have experienced zero growth since the beginning of the 1980s (ESCEC 1986). The average number of children per woman (total fertility rate) for all member states except Ireland is less than two children. By 2000 there will be as many people aged 65 years and over as under 15 years of age (Eurostat 1991).

Ireland still has the highest rate of natural increase in the EC, at 5.8 per 1,000 inhabitants, but it has been declining since the beginning of the 1980s. In 1989 Ireland was the only EC country that kept its total fertility rate (2.11 children per woman) at a level close to the replacement threshold, but the late start appears to have made the Irish fertility rate fall even more sharply: there was an average of four children per woman until the end of the 1960s. A consequence of these differences in the timing of fertility decline is that Ireland is the only country with a relatively young population in Europe, with a median age of 27.7. In contrast the two countries with the oldest population are Denmark, with a median age of 35.6 and the former Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) with 37.2 (Eurostat 1991).

At present only three-quarters of the number of children needed to replace the present generation are being born. Around half of all households in the EC are either one or two person households, while households having five or more persons constitute only 13.3% of the total. Within the EC only 6.5% of households had three or more children in 1989, and 0.6% had five or more children; the respective values for Ireland were 19.1% and 3.9% (Eurostat 1991).

The number of marriages in the Community fell from 2,194,000 in 1960 to 1,941,000 in 1989, while the fragility of existing marriages has increased. If the trends observed over recent years in the various age groups were to hold for a whole generation, throughout its life-cycle, marriage would cease to be the norm and would involve only half the population (ESCEC 1986). The number of divorces increased from 125,000 in 1960 to 534,000 in 1988 for the EC as a whole. During the 1970s Spain and Italy legalized divorce for the first time, leaving Ireland as the only country in the EC with no such legal provision. The available data suggests that the final proportion of marriages contracted in 1975 and ending in divorce should be more than one in five in France, more than one in four in England and Wales and nearly one in three in Denmark (ESCEC 1986). With the option of divorce, the number of remarriages increased so that in 1987 it was almost double the 1960 figure: 303,000 men and 278,000 women remarried in 1987 as against 183,000 and 146,000 in 1960. In addition to the growth in cohabitation, there has been a big increase in the number of people living alone, as widowers, widows or divorcees (ESCEC 1986). There has also been a significant increase in single parent families, with that parent most often being the mother. The proportion of family units which were one parent families in 1981–82 was 5.8% in Germany and 13.6% in Ireland (Eurostat 1991).

Since marriage has been facing competition from various types of more informal union, the number of births out of wedlock in the EC has increased from 4.5% of live births in 1960 to 17.1% in 1989 (Eurostat 1991). Births out of wedlock as a proportion of all live births varied in 1989 from a high of 45% in Denmark to a low of 2.1 % in Greece and with Ireland having 12.6%. The decline in fertility has had a significant impact on third and subsequent births between 1960 and 1988: the extent of decline was 77% in Portugal, 72% in Italy and 40% in Ireland (Eurostat 1991). Since the 1970s there has been a slight rise in the average age at first marriage, and there has also been an increase of one year in the average age of women at the birth of their first child. Among the most striking features that have characterized the European family in recent decades, therefore, are later childbirth, smaller families and more children born out of wedlock.

A related social phenomenon, for which few data are provided by many EC countries, is the growth in the number of declared legal abortions. In 1988 abortions as a proportion of live births were as follows: Denmark (36.0%), Italy (30.4%), the UK (24.7%), France (21.1%) and the former Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) (12.4 %). Differences between countries can be explained to some extent in terms of changes in the law in relation to abortion.

Causes of fertility decline

Demographic trends indicate that most developed countries are converging towards lower fertility rates and, while there are few significant signs of a foreseeable reversal in these trends, it should be noted that Swedish fertility rates have begun to increase rapidly with the number of children per woman now 2.1 compared with 1.6 in 1983 (Family Policy Studies Centre 1991). Swedish women are opting in large numbers to give birth at ages that were previously regarded as high and medically risky for starting a family. While other European countries may follow this trend in the coming decade, the evidence to date is not very promising.

A society wanting to maintain its population size, without systematically relying on mass immigration, needs a considerable number of families with three children. But the reality is that only a minority of families are in favor of three children. It would appear that a fundamental change in attitudes to life and to the family has occurred in recent decades and children are seen by many as restricting the ability to maintain a certain standard of living (ESCEC 1986). Having a second or third child often requires the mother to give up her job and the loss of a second income during the period of mortgage repayment. With the liberalization of contraception and abortion, many couples reject the idea of having an unplanned child. Various influences have contributed to this transformation, such as the decline in religious practice, increasing materialism and the unrelenting propaganda about ‘overpopulation.’

The post-war generation has become known as ‘the consumer society’ who, upon reaching child-bearing age, adopted a form of behavior which was quite different to previous generations (ESCEC 1986). This was a generation which benefited hugely from the explosion in educational opportunities, but unfortunately many have discovered that a higher level of education has not ensured entry into the workforce. Thus in 1988 there were 12.7 million unemployed persons in the European Community, compared with five million in 1977 (Eurostat 1991). Youth unemployment is particularly problematic, as the following figures for the percentage under 25 years of age who were unemployed in 1988 indicate: Spain (33.8%), Italy (32.1%), Greece (26.1 %) and Ireland (23.6%).

Associated with the rise in the level of education among women came a significant increase in the number of women in paid employment. Between 1933 and 1988 the European labour force expanded by an additional six million women compared with just under two million men. In 1988 more than half the women in the EC were in employment: this varied, however, between 76.2% in Denmark and 39.3 % in Ireland. In Denmark‘s case more than 90% of married women in the age group 25–44 were employed (Eurostat 1991). In 1988 women made up more than half the total number of long-term unemployed in the EC, but the figure for Ireland was only 26.2%. It has been suggested that the difficulties of reconciling the demands of a job with the demands of being a mother is one of the critical challenges facing the future of western society, and that too little emphasis is placed on the importance of parenthood (ESCEC 1986). The concern of policy makers about the extent of fertility decline is expressed by Cliquet (1986) as follows:

In the light of the new opportunities and challenges people are experiencing now, post-industrial societies are not well enough organized and have not yet developed a value system which incites a sufficient number of people to transcend their personal needs with respect to parent-hood to such an extent that they also meet societal needs with respect to long-term replacement.

Consequences of low fertility

While many demographers are still quite tentative in their discussion of the causes of fertility decline, two main consequences of the low European birth rate since the 1960s are becoming quite clear, and are by no means altogether favorable: an increase in population aging and a decline in total population. Although the financial impact of a drop in fertility is favorable in the medium term — in that it results in a reduction of certain financing requirements in education, health and family benefits — in the long term the economic effects are definitely adverse in some sectors and the overall effects are less beneficial than is often supposed. In the early 1970s, when enthusiasm for zero population growth had reached its peak, the general expectation was that a reduction in fertility would result in beneficial economic effects. The experience, however, has been that reduced spending on youth did not, in the countries most affected by demographic decline, result in a positive economic response (ESCEC 1986).

Yet some Irish economists continue to be concerned about the high ratio of dependents in Ireland relative to the economically active population: compared with Denmark, which has less than 100 dependents per 100 workers, Ireland has 220 dependents per 100 workers. This is accounted for by the boom in births in the 1960s and 1970s, by the large proportion of married women working in the home and by high levels of unemployment. While the number of children increased until 1986, there has been a decline of more than 20,000 a year between 1986 and 1990, and an increase in the number of women in paid employment. Thus the ratio of dependents to workers has started to fall. Although many social commentators have isolated Ireland’s high level of fertility as a major contributing factor to the recent high unemployment levels, Walsh (1988) suggests that it is not plausible to attribute the exceptional increase that has occurred to an unusually rapid increase in labour supply. He points out that although emigration eliminated all the growth in the labour force during the 1980s, the numbers of unemployed continued to increase.

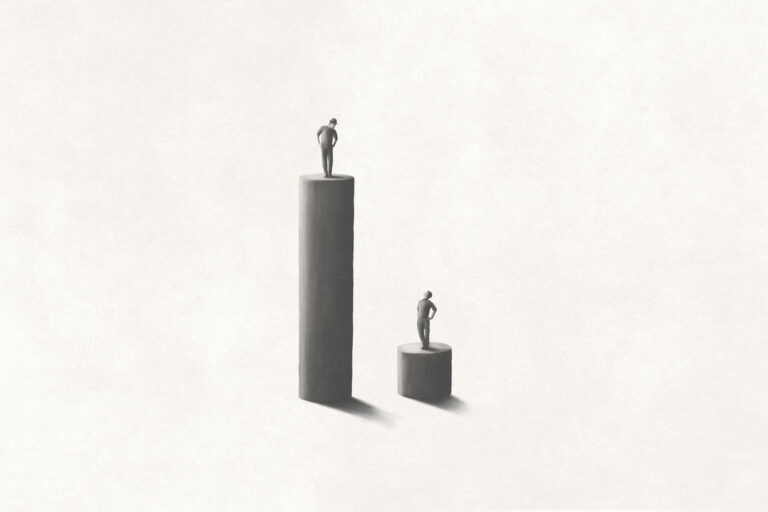

In European countries where fertility decline has been longer established, policy makers are becoming concerned about negative consequences such as a fall in the number of young people entering the labour force. While this may be lessened by a rise in the number of women at work, it is unlikely to offset the full effect in the long term. The growing imbalance in the population pyramid is also likely to lead to major changes in the pattern of demand, with an expansion in demand for products specific to the old and a decline in products aimed at younger age groups. Sectors such as agriculture and food, building and construction and school supplies are likely to be badly affected by these developments.

Among the main consequences of two decades of continuing low fertility is an aging of the population of the European Community, without securing any substantial improvement in affluence. It is also expected that an aging labour force will lead to a heavier burden on the economy. Among the reasons suggested for this are an upward pressure on labour costs because of the smaller pool of younger workers, a decline in geographical and social mobility, and a reduction in the renewal of the economically active population (ESCEC 1986). Associated with these developments are growing doubts about the ability of European economies to maintain their international competitiveness partly due to the loss of a spirit of initiative and innovativeness. It is generally accepted that societies dominated by 50 and 60 year olds are unlikely to be very forward-looking.

The EC’s Economic and Social Committee’s 1986 report on The Demographic Situation in the Community concludes that while people in the more densely populated parts of Europe have been for too long ‘mesmerized by the environmental advantages of a contracting population,’ they now must wake up to the possible long-term disadvantages. Among these would be the additional social security and taxation costs associated with aging, and the reduced ability to master advanced technologies and to compete in export markets.

Aging

In 1989, Futuribles International published a report on the trends and challenges associated with Europe ’s aging population, which concluded that by 2025 as many as one in four Europeans could be 65 years or older (de Jouvenal 1989). There are, however, significant differences between European countries related to the timing of baby boom and of fertility decline. Thus the working-age population has already stopped growing rapidly in France. The report suggested that both the economic system and the working contributors could find the extra burden resulting from an increase in the number of people entitled to benefits difficult to bear. Compared with both the United States and Japan, where the social security system accounts for 29% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Europe’s exceptionally well-developed system accounts for 40%.

While demographic aging is primarily caused by a decline in the fertility rate, an increase in the age at which people die is accentuating the phenomenon. Between 1950 and 1980 life expectancy for women increased by ten years in Spain, France and Italy, largely as a result of a fall in infant mortality rates. Improvements in life expectancy among the old is also the result of reduced mortality in these age groups. The proportion of people who are 75 years and over is increasing steadily, as is the high medical expenditure to which it is linked. In France a difference of three years in life expectancy would mean an increase from 13.4 million to 15.4 million people aged 65 years and over in 2040. Because of the destruction of traditional social networks of solidarity, a huge proportion of the old end up in special homes rather than being enabled to remain in their own homes. It is estimated that 40% of hospitalized old people in France are there for no health-related reason, while 21% of those looking for assistance within their own homes cannot be supplied (de Jouvenal 1989).

Since per capita expenditures on the elderly substantially exceed those on the young, projected increases in the proportion of elderly and very elderly dependents are likely to lead to an appreciably greater increase in the social dependency burden than was implied by a simple head count of the total number in the dependent age groups. On average, total outlays on the elderly in OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries exceed those on the young by a ratio of 2.7, while per capita public spending on health care for those aged 65 and over is on average 4.3 times that for persons aged under 65 (OECD 1988). Population aging, therefore, implies a significant reallocation of resources from programmes serving the young to programmes serving the elderly. French data suggest that by 2010 there could be two non-active persons to every active working person. In 2040 the costs of an old person will be shared between 1.4 and 2.1 adults, compared with just under three adults in 1985 (de Jouvenal 1989). Although most European countries have been promoting the early retirement of older workers for the past two decades, a retirement age of 70 would be necessary in 2040 in France if it wished to maintain its current active-non-active ratio. Or to put it another way, to maintain the current retirement age and the quality of pensions, the rate of contributions would have to increase by 50–80%. Japan is one of the more extreme examples of an aging population: it is estimated that the ratio of pensioners to wage-earners, which was one to eight in 1950, will rise to one in two in 2020 (de Jouvenal 1989). Some policy makers are thinking in terms of the possibility of intergenerational conflict, and there is already evidence of such conflict being generated in the United States by organized interest groups.

Immigration

The record in relation to population projections in the past suggests many reasons why demographers’ projections are usually hesitant and speculative. A major cause of error has been the practice of hypothesizing a zero migratory balance, which has never been the case in practice. Apart from recent refugee movements from Eastern Europe, on the whole Europe has experienced relatively low levels of immigration in recent decades. This situation, however, is unlikely to continue. As Europe faces the challenge of maintaining its economic dynamism in the face of considerable population decline, there is continuing pressure from the Maghreb countries of North Africa where trends in Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria suggest a doubling of the population (from 58 million to 103 million) between now and 2025 (CEC 1991). Much of this pressure is expected to be directed against France and to a lesser extent Belgium and the Netherlands.

It has been suggested that between twenty and fifty million Moslems from the countries around the Mediterranean will arrive in Europe by 2025 (Clarke 1986). Because of its aging population Europe will have little choice but to open its frontiers to young Africans and Asians. Many economists argue that Western Europe, with its aging population and falling birth rate, should welcome rather than fear the injection of able-bodied and relatively cheap labour offered by immigration from less prosperous neighbouring countries. It is unlikely, however, that northern public opinion will welcome such an influx, partly out of racial and cultural prejudice, but also because of fears that such an influx would drive down wages, create unemployment and drive up the price of housing.

There is, therefore, a need for an EC policy in relation to immigration levels, particularly if Europe wishes to become more open to international trade. Some people wonder why a common immigration and asylum policy, rather than economic and monetary union, has not been at the top of the European political agenda. While migratory policy can play a part in short-term structural adjustments, it is not a solution which will safeguard the long-term demographic and cultural survival of Europe. Making good the deficit would require immigration on a massive scale, and the experience to date suggests that immigrant populations tend to adopt the low fertility patterns of the host society. However, since the supplier countries are likely to be African and Asian, this will add to the difficulties of integration.

There are already six million people of North African origin in the EC — half of them in France and 800,000 (mainly illegal immigrants) in Italy — as well as large Moslem communities in Britain and Germany, of South Asian and Turkish origin respectively (Mortimer 1991). These communities are poorly integrated into European society. Hostility to them, and especially to the idea of further immigration from their countries of origin, has become a highly-charged political issue.

Family policy

Because of the consequences of a prolonged period of fertility decline, policy makers in Europe are faced with a series of very difficult choices in a whole range of areas, from the economic and social to the ethical, cultural and political. Some authors see an irreconcilable dilemma between the ingrained pattern of individual freedom in relation to fertility regulation, the widespread desire of females for paid employment and the need of society to reach replacement fertility levels. Among the possible provisions which could be adopted, however, is a more vigorous pro-birth policy.

Research indicates that the recent fall in the birth rate is mainly due to an increase in the number of couples deciding not to have a third child. It appears that many more would be ready to have a third child if society agreed to pay more towards bringing it up (ESCEC 1986). It is suggested that family expenses must be offset by financial transfers, thus recognizing the social role played by individuals who take on the responsibility of raising and educating future generations. Current data suggest that families with four or more children are doomed to disappear. In the former Federal Republic of Germany every second child grows up without the experience of having brothers or sisters, a situation which psychologists claim can present dangers of social deprivation.

If the current trends are to be reversed a political response will be necessary to enable couples to have larger families. France‘s experience in the area of family policy was successful in that it was the country which best resisted the recent trend towards lower births. From being the country with the lowest birth rate in Western Europe in the inter-war period, France now has one of the highest. Yet it should be noted that French family policy, which had its origin in 1938, while favouring a certain recovery in the most malthusian families, has not hindered the reduction in the number of large families (Beaujeu-Garnier 1978). The limited effect of French policy continued until the end of the 1960s and can be seen in the following data: the number of couples having one child rose by 2%, but for those with two children the rise was 22%; for three children, the rise was 6%; and for four, there was a reduction of 2% with a continuing reduction for larger families.

Recent data from the Family Policy Studios Centre in London indicate that, despite child benefits in Ireland being among the lowest in the European Community, Ireland is still top of the EC league with 2.1 births per marriage. Regulations guiding the allocation of financial aid for family responsibility were drawn up quite some time ago, and they are not necessarily compatible with present-day economic and social conditions.

Conclusion

Public awareness of demographic trends in Western Europe continues to be strongly influenced by thinking that was prevalent in the 1970s, when the perceived ‘advantages’ of zero population growth were being strongly promoted. Since then heightened awareness of environmental problems and of high levels of unemployment resulting from economic recession has continued to impact on public opinion in relation to population growth. Nevertheless the long period of fertility decline throughout Europe since the 1960s has had a negative effect on economic development, and new policies are required to reverse this trend.

Among the more serious consequences of low fertility is the aging of the population and the associated imbalances in the population pyramids of European countries. The impact of this process varies throughout Europe because of timing differences in the trend toward fertility decline. Negative consequences, however, such as a shortage of young workers to renew the labour force and to maintain competitiveness through innovation, are beginning to be felt throughout much of Europe. The increased burden associated with supporting an older population by fewer workers could give rise to intergenerational conflict. Changes in the balance between age groups is also affecting particular sectors of the economy — such as agriculture and food and building and construction — because of falling demand. Policy makers are faced with difficult options: they must either open up the European Community to massive immigration from African and Asian countries or promote a vigorous pro-birth policy. Both options are likely to be pursued, but a fundamental change in attitudes towards family policy is required before a significant impact is made on fertility levels in Western Europe.

References

Beaujeu-Garnier, J. (1978), Geography of Population, 2nd ed., London, Longman.

Clarke, R. (1986), “Population imbalances: the consequences,” Forum (Council of Europe), 1, V-VII.

Cliquet, R.L. (1986), “Fertility in Europe: trends, background and consequences,” Forum (Council of Europe), 1, XII-XV.

Commission of the European Communities (1991), Europe 2000 — Outlook for the Development of the Community’s Territory, Brussels.

de Jouvenal, H. (1989), “Europe‘s ageing population — trends and challenges to 2025,” Futures, (Special Issue), 21, 3.

Economic and Social Committee of the European Communities (ESCEC) 1986, The Demographic Situation in the Community, Brussels.

Eurostat, Demographic Statistics 1990 (Eurostat, Statistical Office of the European Communities, Luxembourg) and A Social Portrait of Europe 1991, Luxembourg.

Family Policy Studies Centre (FPSC) 1991, FPSC Report, quoted in Sunday Business Post, 4 August.

Mortimer, E. (1991), “The immigrants we need,” Financial Times, 16 October, 23.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 1988, Ageing Populations — the Social Policy Implications, Paris.

Walsh, B. (1988), “Why is unemployment so high in Ireland today?” Perspectives on Economic Policy, Centre for Economic Research, University College Dublin.